Fire, Fuel, and Second Chances… The Origins of the Hoover Nozzle and Ring Near Brown Field, San Diego, California May 25, 1978  On February 15, 1963, after two years of planning and preparations, the San Diego Aerospace Museum opened on the grounds of the 1915 Panama–California Exposition in the city’s vast urban Balboa Park. On February 15, 1963, after two years of planning and preparations, the San Diego Aerospace Museum opened on the grounds of the 1915 Panama–California Exposition in the city’s vast urban Balboa Park.

By 1978, the Aerospace Museum’s collection contained vintage airplanes, relics, and artifacts highlighting San Diego’s contributions to the history of aviation and manned flight. Items dated from the construction of Charles Lindbergh’s “Spirit of St. Louis” by San Diego’s Ryan Aircraft Company, to rocks taken from the surface of the moon. The museum’s management noticed the growth and sought to move the collection to the larger Ford Building, also in Balboa Park, which was built for the 1935-36 California Pacific International Exposition. With the plan approved, the museum accumulated new aircraft and started to relocate items from the Electrical building. But on the night on February 22, 1978, everything changed. At about 7:55 p.m., two teenagers were seen running from the two-story, Spanish Baroque-style wood and stucco building. Witnesses reported seeing them igniting papers and stuffing them into a vent on one of the arcade pillars at the front corner of the building.  The fire department received the first alarm at 8:14 p.m. and dispatched three engine and two truck companies, however the fire had already made considerable progress and a second alarm was sent at 8:27 p.m., bringing in three more engine companies, one truck and a rescue company. A valiant attempt by these firefighters was made to rescue artifacts and display cases from the building, but fire broke through the ceiling and raged up at the back of the building, driving them outside. A third alarm sounded at 9:22 p.m., bringing three more engine and two truck companies. The force, totaling more than 80 firefighters, fought the conflagration but, by 10 p.m., the building was a skeleton of charred timbers studded with embers. Destroyed in the fire were a replica of the Spirit of St. Louis, a 1928-PT-3 Army trainer, a Japanese Zero, a Curtiss “Jenny,” a Mercury space capsule, and a library of aviation books valued at over $1 million. Both a pen flown to the moon on Apollo 11 and a moon rock sample collected by astronauts on the Apollo 17 moon flight survived the fire. Phoenix Flight... The day after the fire, San Diego Mayor Pete Wilson stood in front of the black rubble and ash of the Electric Building. He addressed an audience of business and industry leaders and called for pledges of support for the reconstruction of the museum. He launched a plan resulting in the formation of the Aerospace Recovery Fund, known as the "Aer-Fund," and kicked off the efforts by hosting a luncheon and donation drive. Museum officials predicted that “like a phoenix,” the Aerospace Museum and Hall of Fame would rise out of the ashes. While donations began to stream in from all over the country as attics and garages, closets and storerooms were emptied of aviation treasures and sent to the renewed museum; it was going to take cash - an estimated $10 million. Fundraisers, large and small, were held throughout the region. And the aviation community organized their support – in the form of an air show, set for Memorial Day weekend in May.  Described by Aer-Fund officials as the community’s "most visible and spectacular” fund raising event, the benefit airshow was held at Brown Field, a former Navy base in Otay Mesa just north of the Mexican border. Sponsored by the San Diego Squadron of the Combat Pilots Association, it featured flyovers of vintage, WWII combat, experimental and current-day military aircraft, as well as aerobatic demonstrations, parachute jumps, and glider acrobatics. Military and civilians provided aircraft for static display, sentry dog demonstrations were presented, and old aviation movies shown. The Marine Corps Recruit Depot Band provided musical entertainment while vendors sold aviation artifacts, souvenirs, and refreshments. Described by Aer-Fund officials as the community’s "most visible and spectacular” fund raising event, the benefit airshow was held at Brown Field, a former Navy base in Otay Mesa just north of the Mexican border. Sponsored by the San Diego Squadron of the Combat Pilots Association, it featured flyovers of vintage, WWII combat, experimental and current-day military aircraft, as well as aerobatic demonstrations, parachute jumps, and glider acrobatics. Military and civilians provided aircraft for static display, sentry dog demonstrations were presented, and old aviation movies shown. The Marine Corps Recruit Depot Band provided musical entertainment while vendors sold aviation artifacts, souvenirs, and refreshments.

James Appleby and Eric Schilling, flying replicas of the German Fokker tri-plane and the French Neiuport 28, conducted a mock World War I dogfight. A two-hour aerial show was planned for each day of the event starting at 1 p.m. The capabilities of a sailplane were demonstrated by T.C. Steckbauer, in a series of maneuvers in his Schweizer built 1-26E, Steve Nelson demonstrated the aerobatic capabilities of his homebuilt “Super Fli" midget plane, Debbie Gary flew her Bellanca Super Viking, and Jim Raymond performed aerobatics in his World War II AT-6 Texan. But headlining the performances was Robert Anderson “Bob” Hoover - conducting his famed one-wheel landings in the Shrike Commander and a series of precision aerial maneuvers in his trademark yellow P-51 Mustang.  R. A. "Bob" Hoover It is impossible to describe Hoover’s storied aviation career briefly. Born in 1922, he learned to fly in Tennessee while working at a local grocery store to pay for the flight training and enlisted in the Tennessee National Guard, earning a pilot training slot with the United States Army Air Forces. While World War II broke out, his first major assignment was flight testing newly-assembled aircraft ready for service. He later became a fighter pilot, flying British-built Spitfires over the Mediterranean Sea. In early 1944, his plane malfunctioned, and he was subsequently shot down by a German Fw 190. Captured and taken prisoner, he was sent to a German prisoner-of-war camp, Stalag Luft 1, in Barth, Germany. Sixteen months into his imprisonment, he escaped from the prison camp. On the run, he stole an Fw 190 from an unguarded airfield and flew to the Netherlands, crash-landing it. After the war, he was assigned to flight-test duty at Wilbur Wright Field near Dayton, Ohio. There he impressed and befriended Chuck Yeager. When Yeager was later asked whom he wanted for flight crew for the supersonic Bell X-1 flight, he named Hoover. Hoover became Yeager’s backup pilot in the Bell X-1 program and flew chase for Yeager in a Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star during the Mach 1 flight. Hoover left the air force for civilian jobs in 1948. He worked as a test & demonstration pilot with North American Aviation, visiting many active-duty, reserve, and Air National Guard units, and went to Korea to teach pilots flying combat missions in the Korean War how to dive-bomb with the F-86 Sabre.  In the early 1960s, Hoover began flying a North American P-51 Mustang at air shows around the country but became best known for his demonstration of the capabilities of the Shrike Commander, a twin piston-engine business aircraft that had developed a staid reputation due to its bulky shape. In the early 1960s, Hoover began flying a North American P-51 Mustang at air shows around the country but became best known for his demonstration of the capabilities of the Shrike Commander, a twin piston-engine business aircraft that had developed a staid reputation due to its bulky shape.

Hoover showed the strength of the aircraft as he put it through rolls, loops, and other maneuvers, which most people would not associate with executive aircraft. As a grand finale, he would shut down both engines and execute a loop and an eight-point hesitation slow roll as he headed back to the runway. Upon landing, he would touch down on one tire followed gradually by the other. After pulling off the runway, he would restart the engines to taxi back to the parking area. Gone Flyin' On the afternoon of Saturday, May 25, 1978, Hoover had just completed performances in his P-51 and the Shrike Commander before an audience of 6,000. Having an appointment back at his home airport of Palomar, Hoover coordinated fueling his Rockwell 500S “Shrike Commander,” registered as N2300H, so he could leave right after the show was completed. When the young man asked how much fuel Hoover needed, he said he wanted precisely sixty gallons, adding ‘“That’s 100 octane.”  After Hoover’s performance, the pilot went to the airport manager’s office, where he received a phone call from the same young man, confirming that 100 LL (low lead) was all right for the airplane. Hoover confirmed that was correct, which the manager relayed over the phone. After Hoover’s performance, the pilot went to the airport manager’s office, where he received a phone call from the same young man, confirming that 100 LL (low lead) was all right for the airplane. Hoover confirmed that was correct, which the manager relayed over the phone.

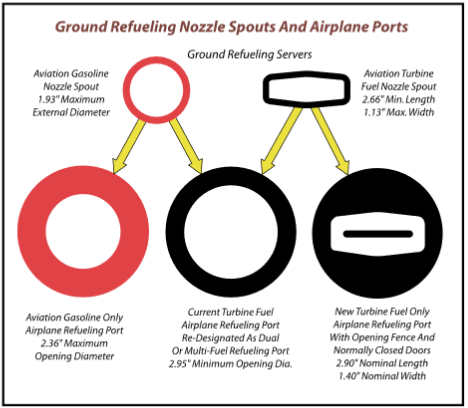

Hoover had a practice of being present whenever the airplane was being serviced but was held up when coming out of the airport manager’s office. By the time he got to the Shrike, the fuel truck was pulling away. Hoover asked if the fueling was done, to which the line service boy replied, “Yes, sir. It was sixty gallons precisely.” Hoover loaded his two passengers aboard and started the two 290 horsepower Lycoming IO-540 air-cooled flat-six piston engines. Taxiing out, scores of aircraft were ahead of him, awaiting clearance to depart from the field. But as soon as he called in, the tower said, “Mr. Hoover, we want you to taxi to the head of the line.” Initially, Hoover was hesitant, not liking to leapfrog ahead of other pilots. However, since he was short for time, he accepted the tower’s offer, taxied on to the runway, ran up the engines, and made a smooth takeoff, heading north. As Hoover recalled, “Everything was normal and checked out perfectly. All of a sudden, at about three hundred feet, I realized I didn’t have any power in the Shrike. I started losing airspeed.” Instantly, he released the back pressure on the Shrike control yoke, but “couldn’t understand what was happening,” he recounted in his autobiography. “Everything checked out. The manifold pressure was right where it was supposed to be. The RPMs were at the right setting. The fuel pressure and oil pressure were in good shape. Even though the gauges indicated that nothing was wrong, I knew something was. I started looking for a place to land. That would not be easy.” But Brown Field is atop a mesa, surrounded by deep ravines, and returning to the airport was out of the question. Hoover’s two passengers tried to remain calm, but were frightened, thinking that whatever that was going to happen would end poorly. “Mr. Hoover,” they asked more than once, “are we going to make it?” Hoover assured them they would, relying on his decades of experience in anticipating trouble. He promptly pushed the control yoke forward to accelerate and maintain the plane’s best glide speed until it reached the very end of the ravine. As Hoover bled off the plane’s airspeed, he lowered the landing gear and wing flaps to minimize the forward speed and inertia on impact. Down in a V-shaped ravine, it measured a thousand feet wide at the top, narrowing down to nothing at the bottom. Hoover flew down to the bottom to maintain the best glide speed, and pulled the plane up, placing it into the side of the ravine. The plane didn’t travel very far at all before hitting a rock pile that caved in the nose and ripped the instrument panel from its mounts and onto Hoover’s shins. Neither the passengers nor Hoover were hurt. At the trio sat and awaited rescue, Hoover pondered what had caused the lack of power. He quickly deduced that there was only one possibility: the plane had been serviced with jet fuel instead of gasoline. To confirm his suspicions, Hoover went around to the side of the airplane and opened the drain valve. Leaning down, he took a whiff of the fuel and was greeted with the distinct aroma of jet fuel. The plane had been able to take off with the remaining aviation fuel in the engines and fuel lines, but as soon as the jet fuel reached the engines, they cut out! Hoover quickly recall the young man he had asked to service the airplane and realized that he must have known by then what had happened as Hoover had informed the tower of the emergency. Within minutes, rescue helicopters hovered over the wreckage, and the threesome climbed up the ravine to be transported back to Brown Field. An Expensive Lesson... After making sure the Strike would be protected from theft, Hoover asked, “Where’s the line boy who serviced my plane?” Everyone seemed reluctant to tell him, apparently afraid that the airshow performer wanted to chew him out or be unkind to him. Finally, someone said, “He’s outside.” Hoover quickly located the boy, standing by the fence, with tears in his eyes. Hoover went over and put his arm around the youngster and said, “There isn’t a man alive who hasn’t made a mistake. But I’m positive you’ll never make this mistake again. That’s why I want to make sure that you’re the only one to refuel my plane tomorrow. I won’t let anyone else on the field touch it.” And for the remainder of that weekend’s air show, the young man refueled Hoover’s P-51 without any further incident. Retired Air Force Brig. General Thomas M. Knoles, III, former fighter pilot and director of the airshow, noted that the three-day event netted the Recovery Fund over $27,000, and plans were made to repeat the feat the following year. When the National Transportation Safety Board investigation (LAX78FA053) concluded, its probable cause agreed with Hoover’s assessment: the improper servicing of the aircraft by ground crew personnel with the inappropriate fuel grade. Contributing to the accident, however, was the pilot’s inadequate preflight preparation and/or planning. Hoover brought another Shrike Commander, registered as N500RA, in 1979. On February 22, 1980, on the second anniversary of the devastating fire, the new San Diego Aerospace Museum and International Aerospace Hall of Fame formally opened its doors again, with a smaller but growing collection, in its current home in the former Ford Building. Amongst the display collection is a new reproduction of the Spirit of St. Louis, specially built for the museum. On June 28, 1980, the first members of the public were welcomed. In 1982, a replica of the Electric Building, the $8 million Casa de Balboa, was constructed with modern fire-suppression equipment. Preventing a Repeat Performance...  In the wake of the accident, Hoover promoted the “Hoover Nozzle,” to be used on refueling equipment dispensing jet fuel. Designed with a flattened-bell shape, it cannot be inserted in the filler neck of a gasoline-powered aircraft with the “Hoover Ring” installed. The design ensures that jet fuel is not inadvertently pumped into tanks meant for piston-powered engines. In the wake of the accident, Hoover promoted the “Hoover Nozzle,” to be used on refueling equipment dispensing jet fuel. Designed with a flattened-bell shape, it cannot be inserted in the filler neck of a gasoline-powered aircraft with the “Hoover Ring” installed. The design ensures that jet fuel is not inadvertently pumped into tanks meant for piston-powered engines.

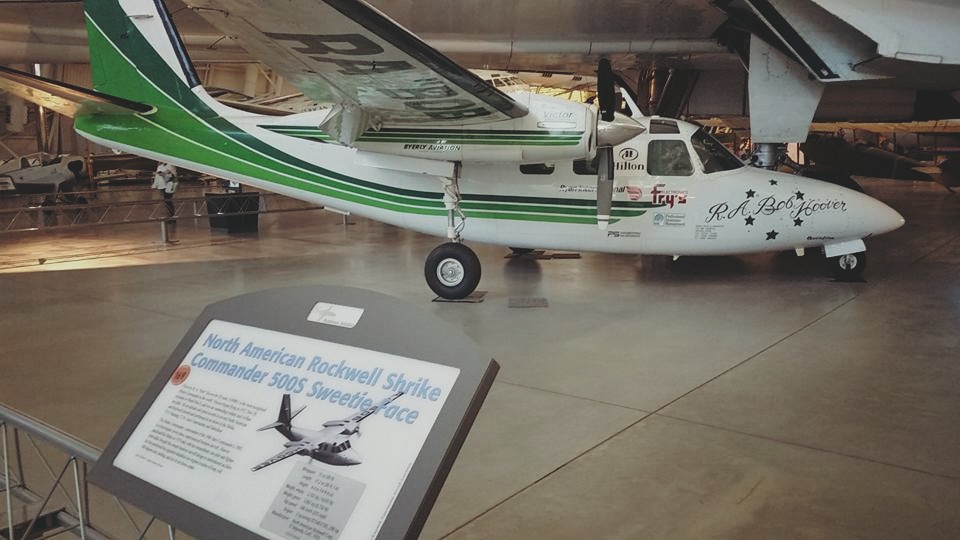

He was the national spokesman, and was featured on posters promoting the fueling hardware, to convince the owners of some 100,000 piston-powered airplanes to narrow their avgas fuel ports to two or 2.36 inches, as well as encourage aircraft fuelers to install 2.6-inch-wide spouts on jet-fuel nozzles The innovation gained the support and funding of the National Air Transportation Association (NATA), the General Aviation Manufacturers Association (GAMA), and various other aviation groups. Today, Hoover Nozzles are now required on jet fuel dispensing equipment in the United States, saving the lives of countless pilots, crew and passengers. Bob Hoover recounted the story of the crash at the end of his autobiography, Forever Flying , published in 1997. However, he misremembered the accident as occurring in 1989. , published in 1997. However, he misremembered the accident as occurring in 1989. Epilogue... Although a reward of $15,000 was offered for information about the person or persons who set the two fires, the culprits were never apprehended. In 2001, the mystery of who set the museum fire was solved. Originally thought to be the work of a serial arsonist, San Diego Fire Battalion Chief Art Robertson learned that the fire was started by three Chula Vista teenagers who confessed they were trying to stay warm. They were not arrested as the statute of limitations for filing an arson lawsuit had already run out.  Bob Hoover was inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame in Dayton, Ohio, in 1988, retired from air show flying in 1999, and gifted Shrike N500RA to the Smithsonian Institute in 2003. In a final flare of air-showmanship, when he and his ferry pilot delivered the Shrike to the Museum’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Virginia – they did a fly-by of the center’s Donald Engen Tower. Upon landing, the Shrike taxied up to the building and, much to the surprise of the audience, rolled directly into the north entrance of the Center. Easily the most recognized Shrike Commander in the world, it remains on display there. Bob Hoover was inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame in Dayton, Ohio, in 1988, retired from air show flying in 1999, and gifted Shrike N500RA to the Smithsonian Institute in 2003. In a final flare of air-showmanship, when he and his ferry pilot delivered the Shrike to the Museum’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Virginia – they did a fly-by of the center’s Donald Engen Tower. Upon landing, the Shrike taxied up to the building and, much to the surprise of the audience, rolled directly into the north entrance of the Center. Easily the most recognized Shrike Commander in the world, it remains on display there.

Hoover passed away on October 25, 2016. A few months before, a life-size bronze statue of Hoover waving his iconic straw hat was unveiled and placed next to his Shrike Commander. Click here to return to Check-Six.com main page |