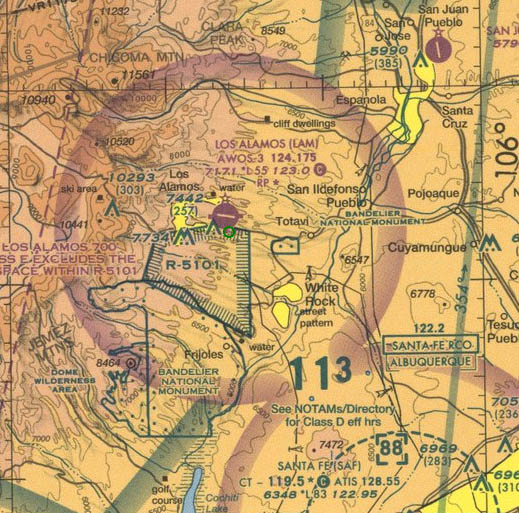

Where Do Baby Bonanzas Come From? The Story of a Piggybacked Pair of V-Tailed Bonanzas Originally Published (abridged) in the May 26th, 2007 issue of "General Aviation News" Text by Christopher L. Freeze - Photos by Pavel Lukes November 6th, 2006 While rare, one small plane landing on another while taxiing or taking off is not unheard of. But what happened on November 6th, 2006, at a small New Mexico airport could be one for the record books. The Land of Enchantment… Los Alamos County Airport (LAM), and its one 5550-foot long asphalt East-West runway sits atop a mesa at an elevation of 7171 feet above sea level. Located just outside of Los Alamos, New Mexico, the untowered airport is also has an unusual neighbor to its south: the Los Alamos National Laboratory (the birthplace of atomic weaponry), and the restricted airspace over its boundaries. The distinctive topography of Los Alamos, with high cliffs, arid soil, and mountains rising to above 10,000 feet to its immediate west, may be great for testing nuclear bombs, but it also forces the use of unusual procedures for aircraft, both arriving and departing, from Los Alamos Airport. All landings are to be conducted to the west and all takeoffs to the east, with no touch-and goes or other training activities being allowed at the field. Also, pilots are asked to report their positions, flying inbound to the field, when passing over either one of a pair of different landmarks near the field, which put aircraft on a route that merges over a highway intersection known to local pilots as the “Y”, and radio communication on the CTAF is requested before landing at LAM. Cutting Variable Costs… Early on the afternoon of Monday, November 6th, 2006, pilot Bob Johnson, a certified ATP with over 15,000 hours flying, and Pavel Lukes, a Czech-born private pilot and real-estate developer, were returning to their home airport in Taos, New Mexico, from a trip to Reno. The flyers had traveled from Reno south to Yerington in Nevada, to fuel their plane, and then south to Tonopah, then over Bryce Canyon, Utah, to Farmington, New Mexico, before their final leg home. Johnson, no stranger to aviation, started a long career as a civilian mechanic on U. S. Air Force aircraft. He progressed into the Aviation Cadet Corps, and served in the California Air National Guard as an enlisted mechanic during the Korean War before transferring to the Air Force. During his twenty-year career with the U. S. Air Force, he flew aboard numerous airframes, ranging from giant Boeing B-52 ‘Stratofortress’ bombers to little Cessna O-1 ‘Bird Dog’ spotting planes. But until he purchased, with a partner, a 1959 Beechcraft Bonanza K35, he had always viewed an airplane as simply a tool to get a job done. Lukes earned his pilot license in 1973, having dreamt of being a pilot since he had been a kid, and had been flying off and on ever since. He entered into the partnership with Johnson for the Bonanza in 2003, and their flight up to Reno had been for the purpose of attending an instrument ground school. Interested in cutting down on some of the costs of their return leg, the pair decided to refuel their plane, callsign N5368E, at Los Alamos, where 100LL avgas sold for less compared to their home airport of Taos, some 50 miles to the northeast.  Johnson asked Lukes if he had ever been to the Los Alamos, to which Lukes explained that he had been to many of the fields surrounding LAM, but never to Los Alamos Airport itself. Johnson then briefly explained the unique traffic pattern and approach system into LAM. An adventurous traveler, and interested in the prospect of savings on fuel, they continued onwards to Los Alamos. Johnson asked Lukes if he had ever been to the Los Alamos, to which Lukes explained that he had been to many of the fields surrounding LAM, but never to Los Alamos Airport itself. Johnson then briefly explained the unique traffic pattern and approach system into LAM. An adventurous traveler, and interested in the prospect of savings on fuel, they continued onwards to Los Alamos.

While en route with flight following from Albuquerque Center, Johnson and Lukes reviewed the Airport Facility Directory entry for Los Alamos, since it was an "unfamiliar airport” to both of them. Johnson had remembered the unusual approach procedures for LAM being broadcast on the AWOS frequency, but when tuned to the weather station’s channel, there was no indication of the uncommon procedure being broadcast. Deciding that the unorthodox approach pattern probably was no longer used, he and Lukes flew as they normally would, approaching the airport from the north, with Johnson making position reports to Los Alamos. Meanwhile, Johnson and Lukes, in their Bonanza, heard no traffic broadcasts on their radio set. Entering the traffic pattern for Los Alamos at 8,000 feet on a right base, the plane continued on its descent towards landing on runway 27. About 50 feet before landing, a shadow moving along the ground caught Lukes’ eye. Their assumption of a traffic free air space was not to last long. Doing It By the Book… As Johnson and Lukes preparing for their landing, James Unruh, a retired park ranger, and commercially-rated pilot with over 5,000 hours, was also approaching Los Alamos from the north, on a flight from Meadow Lake Airport (00V) in Colorado. James Unruh aspired to fly ever since he could remember. An ‘outdoorsy man’, family 8mm films show a young Jim, at age 3, looking to the sky and tracing the path of flying planes. A second-generation pilot, he was determined to learn to fly, and earned his pilot’s license in 1970. Aboard his personally-owned 1963 Bonanza P35, callsign N102H, he too announced that his green and white plane’s position several times, including over the Otowi Bridge, a reporting point known to local pilots. While transmitting on the CTAF frequency of 123.00 for Los Alamos, he announced his intention to land there. Hearing no other traffic on the frequency, he continued on and completed his GUMPS check about a half-mile from the approach end of Los Alamos’s runway 27, all the while scanning the skies for unexpected traffic. He noticed some heavy construction equipment just outside of the runway environment, creating a plume of dust blowing slightly from the south – indicating a slight crosswind. As Unruh continued downwards to land, at about 7 feet above the runway, he began to initiate his landing flare, expecting the smooth ‘chirp-chirp’ of his tire rubber meeting runway pavement. At the same moment, Lukes, who was seated in the right front seat of his Bonanza, continued to notice the shadow crossing his view. Suddenly, Johnson and Lukes’ plane’s windows were filled with the image of another plane’s landing gear! Shouting an expletive warning into his headset - a second before their plane touched down, the landing gear wheel he had spied was now behind his head, and atop their roof, accompanied by an unpleasant crunching sound! As Johnson and Lukes were just beginning to realize what had happened, Unruh’s first thoughts were that he had commenced his landing roll. However, something was very wrong, as his plane was still several feet above the runway. As his plane slowed, it listed and yawed to the right. Still thinking he was “flying the plane”, Unruh applied corrective action, attempting to correct his path to the left, but discovered that his controls were having no effect. His plane’s right wingtip began to drag along the runway’s surface. As he scanned his view, he noticed that, to the extreme left of his vantage point was visible the brown top of another plane beneath his!  Unruh then realized what was happening – “I was still the pilot of my airplane, but also the passenger of someone else’s!” Unruh quickly shut down his plane’s systems, and popped open his door, unable to hear the shouts of Lukes asking him to stop the propeller, wind milling only feet away from his head. The friction of the dragging wingtip was finally unable to overcome the Bonanzas’ inertia, and both craft turned to the right and came to rest about half-way down the runway, right in front of a construction crew working nearby. Unruh then realized what was happening – “I was still the pilot of my airplane, but also the passenger of someone else’s!” Unruh quickly shut down his plane’s systems, and popped open his door, unable to hear the shouts of Lukes asking him to stop the propeller, wind milling only feet away from his head. The friction of the dragging wingtip was finally unable to overcome the Bonanzas’ inertia, and both craft turned to the right and came to rest about half-way down the runway, right in front of a construction crew working nearby.

An Unlikely Formation Flight… Unruh was able to exit his plane, and circled around to the pilot’s side of the bottom Bonanza, where he saw an amazed Johnson in the pilot’s seat. Luckily, the construction workers had a large dry chemical fire extinguisher on hand – in the event of a sudden fire. After a brief conversation through Johnson’s vent-window door, the sound of sirens in the distance could be heard as a fire crew from Los Alamos raced to the scene. Johnson formulated a plan for he and Lukes to exit their plane through the baggage compartment door, but the arrival of the emergency response units changed all that. Wellford Martinez, a firefighter with the Los Alamos Fire Department, said his office received a call about the incident at 2:59 PM. He arrived on the location of the planes, and was one of the first to see the strange sight of the two planes - one on top of the other - resting sideways in the middle of the runway. Assuming command of the incident, it took the crash crew from the Los Alamos Fire Department only 10 minutes to extract Johnson and Lukes from their plane, tearing through Johnson’s window, and further damaging the plane’s aluminum frame.  Surprisingly, no one, aboard either plane, was injured in the “pile-up”. Even the damage to both planes was limited: very little oil was spilled, and the only visible damage was three broken windows, bent antenna, wrinkled skin on top and leading edge of the wing, a nicked propeller, and a crumbled roof, to the bottom plane. The topmost plane suffered a slashed tire, several nicks to the nose wheel rim, damage to the outermost section of the right wing spar, and some of the control surfaces. Surprisingly, no one, aboard either plane, was injured in the “pile-up”. Even the damage to both planes was limited: very little oil was spilled, and the only visible damage was three broken windows, bent antenna, wrinkled skin on top and leading edge of the wing, a nicked propeller, and a crumbled roof, to the bottom plane. The topmost plane suffered a slashed tire, several nicks to the nose wheel rim, damage to the outermost section of the right wing spar, and some of the control surfaces.

In an interview with news media on the scene of the misfortunate run-in, Johnson stated that everyone involved in the mishap was very lucky - "It's a rare occasion that something like this happens and no one gets hurt." Investigators from the FAA ordered the airport closed down until further notice, which came the following morning. However, the word at the airport must have traveled slow for about two hours after the aeronautic fender-bender, one of the responding firefighters had to intercept a small plane taxiing towards the runway, seemingly unaware of the airport’s closure from the earlier incident. Undoing What Has Been Done…  Having been warned by an insurance adjuster of the potential for further damage to either plane, a specialist was called in to perform the awkward task of separating the Bonanzas. Completing the delicate process was Chris Jarman and “Air Transport” of Phoenix, Arizona. Jarman placed two heavy-duty straps around the fuselage, to the front and aft of the wing roots of Unruh’s Bonanza. Then, the airplane was slowly and meticulously lifted from the other plane by a custom-designed truck-mounted boom in a process taking just over 30 minutes, and with no additional damage to either plane. Having been warned by an insurance adjuster of the potential for further damage to either plane, a specialist was called in to perform the awkward task of separating the Bonanzas. Completing the delicate process was Chris Jarman and “Air Transport” of Phoenix, Arizona. Jarman placed two heavy-duty straps around the fuselage, to the front and aft of the wing roots of Unruh’s Bonanza. Then, the airplane was slowly and meticulously lifted from the other plane by a custom-designed truck-mounted boom in a process taking just over 30 minutes, and with no additional damage to either plane.

Days later, both airplanes – no longer mated – flew under their own power to Beegles Aircraft Service in Greeley, Colorado, by Beegles’ trained ferry pilots. The National Transportation Safety Board classified the collision as an incident, and concluded in its investigation that the probable cause was “the failure of both pilots to maintain adequate visual lookout during the visual approach. A contributing factor was the failure of the N5368E's pilot to communicate his intentions on the Common Traffic Advisory Frequency.” One Photo = A Thousand Words… “There are a thousand ways it could have happened – but it happened the only way it could so we lived,” said Lukes. “If either plane had been 20 seconds earlier or later in flight, things would have been completely different.” Unruh stated that, “A person will revert to the training he or she has – the more practice one has, the more likely a pilot will react appropriately in an emergency.” Johnson stated that, in his opinion, “Too many new pilots nowadays rely on GPS, and not their visual, skills. Their heads are in the cockpit, not outside of the airplane – looking.” He correlates a rising trend in aircraft accidents due to increased use of such technology. Nevertheless, photos taken by news reporters and curious on-lookers, as well as Pavel Lukes himself, of the unusual-positioned Bonanzas have served as humorous fodder for several online discussion forums, both aviation and non-aviation alike. Many refer to the sight of the stacked planes as how “baby planes” are made. “You can’t avoid the truth when it is in a picture,” said Johnson, who continues to express embarrassment over photos of the plane pile-up. “Bent airplanes happen for dumb reasons, and I am not shocked by any reason – especially now that I am in that category.” All photos presented here were taken and provided by Pavel Lukes |