The Meaning of a “Little Dog Toy” Over the Arctic Ocean 1 July 1960 Homegrown Roots...  | Crew of RB-47H #53-4281 on 1 July 1960

Front row (left to right): Pilot Major Willard Palm,

Captain Bruce Olmsted, Captain John McKone

Back row: Major Eugene Posa,

Captain Oscar Goforth, Captain Dean Phillips |

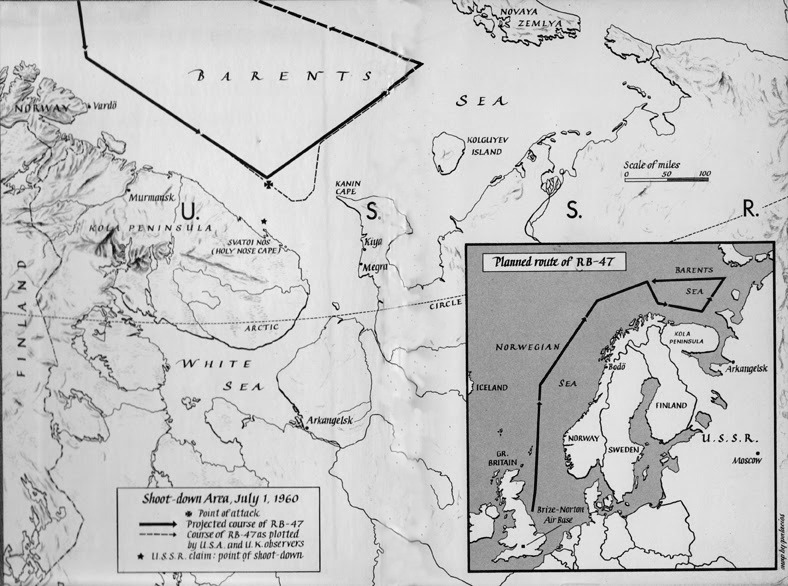

On July 1st, 1960, two months to the day that a CIA U-2 piloted by Francis Gary Powers was shot down over Sverdlovsk, a United States Air Force RB-47H reconnaissance plane, tail number 53-4281, and assigned to the 38th Strategic Reconnaissance Squadron of the 55th Strategic Reconnaissance Wing based at Forbes Air Force Base, Kansas, departed from Brize-Norton Royal Air Force Base in England. The plane was crewed by Major Willard Palm as Aircraft Commander; Captain Freeman B. Olmstead as pilot; Captain John McKone as navigator. Lodged in the converted bomber's bomb bay were tons of electronic gear designed to measure the strengths and weaknesses of Soviet radar defenses, and three “Raven” reconnaissance officers: Major Eugene Posa, Captain Dean Phillips & Captain Oscar Goforth (on his first operational mission). Olmstead was born in Elmira, New York, and brought up in a devout Episcopal family. He earned a bachelor's degree in history from Kenyon College, Gambier, Ohio. He entered active duty with the Air Force in 1957 and attended the service's Squadron Officer School. McKone was a native of Tonganoxie, Kansas, and he graduated from Kansas State University with a bachelor's degree in history in 1954. He was the Cadet Wing Commander for the Air Force ROTC wing during his senior year, and he entered active duty on March 15, 1955, as a Second lieutenant – beginning his career as a Strategic Air Command navigator in April 1956.  A “Ferret” Mission... The flight's planned route took the plane northbound from England over the international waters of Arctic Ocean, where the plane turned east and entered the Barents Sea, northeast of Norway, and continued a track about 50 miles from the Soviet-held Kola Peninsula – all the while over international waters. In the ten years between 1950 to 1960, the Soviet Union had a history of shadowing, “escorting”, and every now and then, shooting down American planes flying over international waters near its borders. In 10 separate incidents, about 75 US Navy and Air Force air crewmen lost their lives flying routine reconnaissance missions. Among such incidents were the shootdown of a Navy bomber over the Baltic in the spring of 1950, and an Air Force C-130 transport that was lured by false radio beams into Soviet Armenia, which was shot down in September 1958.  Soviet pilot Vasiliy Polyakov was on strip alert when he was scrambled flying his MiG-19 fighter, assigned to the 206th Air Division, to intercept an intruding plane north of Murmansk, and west of Novaya Zemlya, in the Barents Sea. He turned toward the plane on an intercept course, but passed about three miles behind it. He approached the plane and was able to identified it visually as an American bomber. The radar course plotted by Capt. McKone called for a turn to the northeast at about 50 miles off Holy Nose Cape at the bottom of the Kola Peninsula; however, the Soviet MiG had returned and was now flying in close formation - 40 feet - off the right wing of the RB-47. He rocked the wings of his MiG in an attempt to signal the Stratojet to land. Failure to Acknowledge... But when the American plane gave no response, the ground navigator gave the command to destroy the aircraft. Flying at 30,000 feet, at a speed of 425 knots, the RB-47 started its turn to the left, Polyakov broke right back towards the Soviet shoreline, and then turned back towards it, and opened fire - shooting up the left wing, engines and fuselage in its first pass, causing the RB-47 to enter a spin. Major Palm and Captain Olmstead were able to pull out of the gyration, and Olmstead immediately returned the attack, but the no match. After a brief fight, the MiG's second firing pass caused the RB-47 burst into flames, sharply rolled upside down, and fell into the evening clouds below. Palm and Olmstead attempted to save the plane once again, but the damage was too serious and the bail out order was given. Two of the officers - Captains McKone and Olmstead - successfully ejected and survived – only to be picked up by a Soviet fishing vessel after more than six hours in their tiny survival rafts. The aircraft commander, however, perished in the frigid waters of the Barents Sea, and the three reconnaissance officers were likely trapped in the converted bomb bay of the plane – thus entombed and carried to the ocean's bottom. The U.S. Air Force were initially unaware that their plane had been shot down. The Air Force, in concert with the Navy and the Soviet Union, conducted a search for the missing plane and crew for nearly a week after it was declared missing, but no trace was found. Revelation! Ten days after the shootdown, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev announced that they had shot down the bomber, and captured the two crewmen, who were now to be tried as spies, "under the full rigor of Soviet law." Major Palm's body, which was recovered during the search, was returned to the United States about a month after the shootdown, and he was buried with full military honors in Arlington National Cemetery, near Washington, D.C. Vasiliy Polyakov, the MiG pilot, later stated that it was a combination of Soviet internal pressure to protect its territory and his belief that the Air Force plane was headed for a secret naval base that resulted in his shoot down, despite the Stratojet's location in international airspace, and over international waters. In short order, the pair were imprisoned in Moscow's dreaded Lubyanka prison, and accused by the Soviets of espionage, punishable by death, for allegedly violating the Soviet Sea frontier, even though their craft had been miles away from it. Name, Rank and Service Number... The pair managed, despite being housed in separate cells while undergoing interrogation, to resist all Soviet efforts to obtain "confessions" through flattery, deceit, and threats of death – although they were not tortured but were interrogated at length nearly every day – in accordance with the Geneva Conventions. They were allowed by the Soviets to see each other only twice, and were denied visitation and access by U.S. embassy personnel. They were instructed not to reveal any information that could have been useful to the Soviets – just their name, rank and service number. Bit by bit, the Soviet handlers allowed some mail to flow to and from family members. But the censors at the prison, and the interrogators, continually tried to get the Air Force officers to indicate regret for reconnaissance mission, hoping to use that as propaganda to make the United States cease similar reconnaissance missions. But the Soviets failed to get the "confessions" they sought as part of the pretrial "investigation” against McKone and Olmstead. In a letter home, McKone – an avid car lover – advised his wife, "About the car, change the oil and filter every 3,000 miles. Grease it every 1,000 miles." In one of his letters home to his wife, Olmstead wrote, "I am kept alone in a cell but am not being abused." Prison, he wrote, "has pretty well shown me that I couldn't quite make it as a cloistered monk. I am given cigarettes, hon, and filters at that. But, oh my, how I long for a good old American cigarette... And I must confess that I wouldn't be averse to a martini." The Routine of Politics...  During their confinement, every two weeks, the U.S. State Department sent notes to the Soviet Foreign Office and asked that the two officers be released. And every two weeks, the notes drew evasive replies from the Soviets. During their confinement, every two weeks, the U.S. State Department sent notes to the Soviet Foreign Office and asked that the two officers be released. And every two weeks, the notes drew evasive replies from the Soviets.

Throughout the ordeal, Captain McKone carried a small plastic toy "Snoopy". About a month after the shootdown, Major Palm's body was returned to the United States. He was buried with full military honors in Arlington National Cemetery in Section 3, Site 2508. Shortly after the inauguration of President John F. Kennedy, high-level talks between the United States and Soviet Union began, and Premier Nikita Khrushchev extended an offer to free Olmstead and McKone quickly – but with three terms: The announcements of the airmen's release must be made simultaneously in Washington and Moscow, with no advance news leaks; the U.S. must publicly declare that it has discontinued its U-2 flights over Soviet territory; and the U.S. must promise not to make “international political capital” out of the prisoners' release. The American Ambassador to the Soviet Union, Llewellyn "Tommy" Thompson, had little difficulty agreeing to the deal, as the U.S. had suspended the overflights since Powers' shootdown, the demand for simultaneous announcements was not difficult to coordinate, and declining to re-state what the U.S. had been pointing out in open sessions of the United Nations would be counterproductive at this juncture. Detente!  Finally, after seven months of imprisonment and shortly after the inauguration of President John F. Kennedy, on January 24th, 1961, the guards at Lubyanka gave the pair Russian suits, heavy wool overcoats and felt hats, and rushed them into a car. They were driven across downtown Moscow to the American embassy, where even the Marine guard did not recognize them, later saying, "They looked like Russians.” They were handed over to U.S. officials – with the Soviets never gotten any information from the pair, or ever having been brought them to trial. Finally, after seven months of imprisonment and shortly after the inauguration of President John F. Kennedy, on January 24th, 1961, the guards at Lubyanka gave the pair Russian suits, heavy wool overcoats and felt hats, and rushed them into a car. They were driven across downtown Moscow to the American embassy, where even the Marine guard did not recognize them, later saying, "They looked like Russians.” They were handed over to U.S. officials – with the Soviets never gotten any information from the pair, or ever having been brought them to trial.

The pair meet with Ambassador Thompson, who briefed them as to the events leading up to the handover, and then rushed to Sheremetyevo Airport to take a KLM flight out of Moscow. The plane, an Electra, was taxiing to the runway when it was rocked by a sudden motion – two tires had blown! The passengers aboard were taken back to the airport terminal, and spares were flown from Warsaw. With every passing minute increasing the possibility of a news leak, McKone and Olmstead were spirited back to the U.S. embassy, with no notice as to when their plane would be ready to depart. They were hidden away in the ninth-floor apartment of the embassy's air attaché, Colonel Melvin J. Nielsen, as electricians were ordered to do phony "maintenance" work on the front-entrance elevator to keep it temporarily out of commission to discourage visitors. Twelve hours later, the Electra was repaired, and the officers were bound for Amsterdam. Moments after they had taken off, Colonel Godfrey McHugh, White House Air Force aide, telephoned the wives of McKone and Olmstead to report that their husbands were free, and President Kennedy held a press conference announcing that the crewman were winging their way home. From Amsterdam, McKone and Olmstead were flown via an Air Force Globemaster to Goose Bay, Labrador, where the weather forced an overnight layover before taking a Constellation south to Washington, D.C. The layover gave the two men time to outfit themselves with new Air Force uniforms at the base post exchange, and their doctors a chance to convince themselves that both men were in good mental & physical health.  | | Air Force Captains John McKone and Bruce Olmstead deplane at Andrews AFB, Maryland |  | Captains John McKone, Bruce Olmstead, and their wives are honored at the White House by

Vice President Lyndon Johnson, First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy,

and President John F. Kennedy |

A Hero's Welcome... When the two men arrived in the snow-filled nation's capital the following afternoon, they walked down the steps from their plane, tossed a brisk salute to President Kennedy and located their wives. Despite the Air Force brass and government dignitaries on hand for their arrival, both of the former captives kissed their wives passionately. Later that same day, both couples drove to the White House, where Jack Kennedy waited for them on the snow-swept North Portico, where they had coffee in the Red Room with Jacqueline Kennedy, Vice President and Mrs. Johnson, Air Force Secretary Eugene Zuckert and Kansas Representative J. Floyd Breeding. The President advised the two officers to head south for a vacation. "You had lipstick all over you," he told McKone, recalling the young officer's reception at the airport. But after seven months of solitary confinement, McKone said, "I don't think either one of us has anything to complain about one bit." The two captains, with their families, returned to their Kansas homes that next weekend, to resume their Air Force careers. The More Things Change... Some in the new Kennedy administration took the release as a good sign from the Soviet Premier and his country. But Secretary of State Dean Rusk worried, "The one thing I fear is that Americans will think the Russians have really changed, that they're softening, that the worst is over." Words that would echo in the days leading up to the Cuban Missile Crisis nearly two years later. McKone retired as a Colonel in the Air Force in September of 1983. Among his many assignments, Colonel McKone was Base Commander, Ellsworth Air Force Base, S.D., and Air Base Wing Commander, Offutt Air Force Base, Neb. His military awards and decorations include the Legion of Merit with one Oak Leaf Cluster, Distinguished Flying Cross with one Oak Leaf Cluster and the Prisoner of War Medal. Olmstead also retired as a Colonel, in October of 1983. Among his assignments were Defense Intelligence Agency, Pentagon, U.S. Air Attaché and U.S. Defense Attaché, U.S. Embassy, Copenhagen, Denmark. His military awards and decorations include the Distinguished Flying Cross, Purple Heart and Prisoner of War Medal. Years later, as a result of their involvement in the incident, Olmstead and McKone received the Prisoner of War medal in 1996, and Silver Star medals in 2004, as well as the Distinguished Flying Cross. McKone died in 2013, Olmstead in 2016. Both were buried with full military honors in Arlington National Cemetery - McKone in Section 60 Site 10471, Olmstead in Section 47, site 765. |